During World War II, government scientists at a research facility called Porton Down began testing cloning technology. This facility was initially used to test chemical and biological weapons, sometimes on our own British troops.

The facility was also used to research chemical and biological weapons seized by Allied forces from German stockpiles. It is not known if the first tests of cloning technology were inspired by British or German innovation, but cloning testing began while the war was still ongoing.

The cloning research progressed slowly and it was not until after the War ended that the first living clones were produced. Scientists first began by cloning domestic animals created from fusions of cloned eggs and DNA birthed from living mothers.

The initial goal of the cloning project was to create cloned organs and limbs that could be transplanted for injured soldiers and casualties of the war. However, scientists found that they could not succesfully clone individual organs and needed to clone a body to carry them.

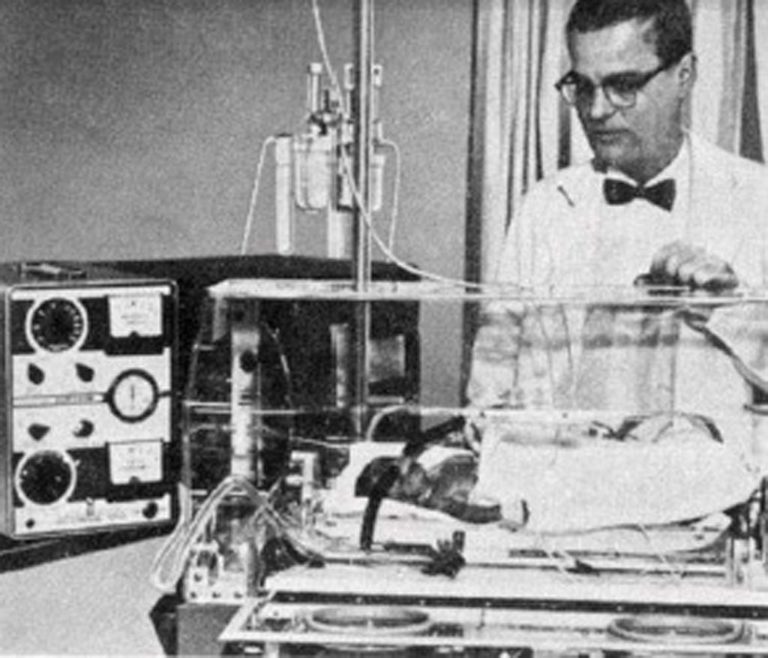

The first successful live birth of a cloned human being took place either on August 26 1952 or November 1 of that same year. The child was named Isaac and was born with a lung deformation. Isaac died appox. 1 week after birth, living on a ventilator all his life. For the scientists of Porton Down, however, his death was not in vain. The pace of research only quickened after his sacrifice.

Sometime after Isaac's death, the project was expanded significantly due to the possible reshaping of the workforce, healthcare, or whatever else the government needed to call it to justify the cloning research.

The next major developments came fast- general health improvements led to children being born with no complications by 1953, and by 1954, the project had led to the birth of approx. 20 cloned children. These children were observed by researchers and their families (the "first families of cloning,") and later children would be indiscriminately entered into the foster system.

In 1959, a Bill was proposed by MP Richard O'Neill that would ban human cloning. This bill was rejected by Parliament. O'Neill intended for his bill to expose the cloning project of Porton Down to the larger government. It did. In 1960, Parliament passed a bill proposed by MP George Berkshire that opened the research of Porton Down to the general healthcare field and classified clones as a new social class- the bill did not define whether or not these clones would have the human rights given to most. This lack of a definition would be the source of many court battles to come.

The final major development in cloning research was the first successful birth of a clone from an artifical womb in 1962. Now, the entire process of "conception" and "birth" was artifical and human-controlled.

The first clone-to-human organ transplant took place the same year. An unnamed clone in their teens provided a kidney to a 30-year-old resident of Liverpool named Regina Harrelson. The organ transplants only grew in number and intensity and by the 1970s the idea of clones being birthed just for organ transplants was no longer taboo but instead the leading idea of clone research.

The 1970s also proved to be the most contentious decade for protests for and against cloning.

By the 1980s, cloning had become so commonplace 50% of organ transplants were from clones. By the 90s, nearly 90% of transplants were sourced from clones. During these decades, the way the clones were raised and the way clones "lived" were drastically changed.